Stalking Awareness Month highlights a dangerous form of abuse

MOSES LAKE — January is Stalking Awareness Month and those who work with victims want people to know that it is a serious issue and there is help available.

“Stalking is usually a factor in a domestic violence victim’s experience,” said Abraham Tapia, a legal and community advocate with New Hope, which provides domestic violence support in Grant and Adams counties. “Following them around town, trying to access their social media.”

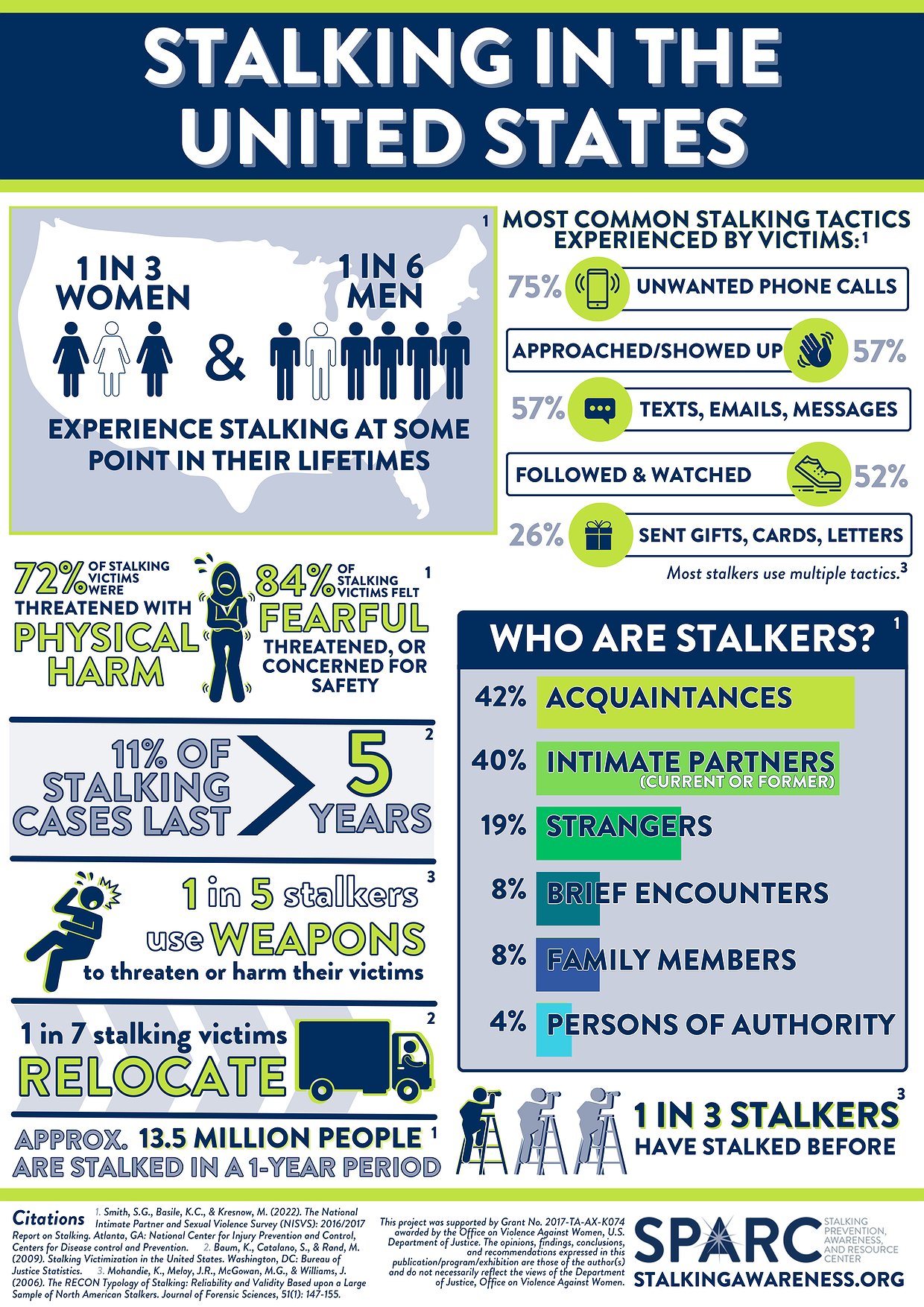

The month is meant to draw attention to an especially dangerous form of abuse. One out of three women in the U.S. will experience stalking at some point in their lives, according to statistics from the Stalking Prevention, Awareness, & Resource Center, and one in six men. More than a third of stalking cases involve a current or former intimate partner.

Washington state law defines stalking as intentionally and repeatedly harassing or following another person and causing them emotional distress. That goes a long way beyond merely Googling their name or checking out their public social media pages, said Grant County Sheriff’s Office Public Information Officer Kyle Foreman.

“It’s taking action to try to infiltrate their life and find out information about that person and use it in a way that’s not in good faith,” Foreman said.

There are cases where stalkers are acquaintances or even total strangers, according to SPARC, but those don’t happen much in the Basin, Tapia said.

“For the most part it’s somebody who’s known to the victim who’s doing the stalking,” he said. “We have had people be stalked by a neighbor or by someone in the community, and those will take a little more work to identify who the stalker is. But in my experience, it’s rare to see that kind of case. It’s usually people who know each other.”

As a component of domestic violence, stalking adds a whole new dimension to the abuse. Physical abuse requires the perpetrator to be actively present, but the psychological effects of stalking can keep on traumatizing the victim in between physically violent episodes. It’s also a lot harder to document for the authorities, Tapia said.

“(Stalking) is sometimes a difficult thing to prove versus an abuser who physically assaults a victim,” he said. “There’s bruises and there’s marks on their body, whereas stalking is more of a psychological abuse. And unless they have (the stalker) on camera following them around town, it’s harder to prove.”

It’s scary enough being followed by your abuser, Tapia said, but when there’s not enough evidence for the police to take direct action, the feeling of helplessness makes everything harder.

“They can report that their ex was following them around town or showing up at their work,” he said. “But usually, the people who are stalking are a little bit more equipped to avoid detection in what they’re doing. A lot of abusers who will just deny it outright or give another explanation as to why they were in the same place.”

That’s even more prevalent in a small, rural community like those in the Basin, Tapia said. An abuser is likely to know the victim’s daily routine, and there are only so many places they can be. Also, in today’s high-tech world, they don’t even have to be in the same place to stalk their victim.

“Showing up (at the store or restaurants) whenever they’re going someplace, that’s the traditional stalking,” said Moses Lake Police Captain Jeff Sursely. “But you can (also) be on their (social media) pages, their feeds, using fake profiles. There’s a lot of different ways to harass somebody digitally.”

Nearly half of stalking cases include both in-person and electronic methods, according to SPARC. An intimate partner may have their victim’s social media or bank account password or be able to obtain it. They may go into social media spaces and harass or humiliate their victim, or they may use it to find out where their victim will be at a given time, so they know where to follow them. They may impersonate the victim or contact their friends and family to smear their reputation or damage their personal relationships.

A technique Sursely said he’s seen is the use of electronic tracking devices. For a small price, you can get a small disk about an inch and a quarter in diameter that emits a signal that its owner can track with their cell phone. Some operate only within a short range; others can tap into satellite networks and let their owners know their location anywhere in the world. It can be attached to a phone, a key ring or a wallet to make sure its owner doesn’t set it down and walk away. It can also be slipped into a purse or attached to a car.

“We’ve had a couple of cases where people were using (tracking tags) to follow people,” Sursely said. “Usually, it’s somebody who figures out that it’s occurring and then comes and reports that their phone is showing a (tag) within so many feet.”

There are apps that can detect if a tracking tag is being used in the vicinity, Sursely said.

Anyone who thinks they’re being stalked should immediately contact New Hope or the police, Tapia said. New Hope has resources for helping a victim get a protection order in place. That protection order can make all the difference, he said.

“It puts the power in their hands, and then they can start reporting (the activity),” he said. “And if they can report it in a way where they have some kind of proof that the stalking did occur, then charges could follow through for the violation of a protection order as well.”

If there’s a protection order in place, stalking becomes a felony under Washington law, which gives law enforcement more tools to put a stop to it.

New Hope has a screening process advocates use to assess the danger a victim is in and what steps need to be taken to ensure their safety. Sometimes the risk is relatively low, but other times, the victim has to take some serious action. Some people have to move out of the area, but even then, often their harasser can find their new address, and it will all start up again. The State of Washington has a program called the Address Confidentiality Program that allows a person at risk to keep their address out of public records. A participant is assigned a post office box that they can use as their legal home, work or school address. All mail will be sent there, and then forwarded to the participant’s actual address. That actual address is stored in a secure facility with no public access, according to the state’s website. The ACP program can also make sure the person’s information is kept out of publicly available records like voter registrations or marriage records that are ordinarily available online. New Hope advocates can help with applying for that program, Tapia said.

“Stalking is emotional abuse in any form,” Tapia said. “It can be just as damaging as physical abuse because it sticks with a client in a psychological sense; it’s an infliction of fear for the victim. A bruise, it’ll go away. But someone who’s adamant on stalking and keeping a victim under surveillance, it’s pretty malicious.”

Anyone who thinks they might be stalked, or who is experiencing any other sort of domestic abuse, can contact New Hope in confidence 24 hours a day at 1-888-560-6027, or come to the New Hope office weekdays at 311 W. Third Ave, Moses Lake. More information is available at New Hope’s main line, 509-764-8402.