Facing the past

MOSES LAKE — When you buy a home, there are often neighborhood covenants that come with the property. Sometimes you have to have your house set a certain distance back from the street, or you can’t put up a shed as a second residence, or you can’t run certain kinds of business out of the house. And on paper, at least, sometimes you have to be white to live there.

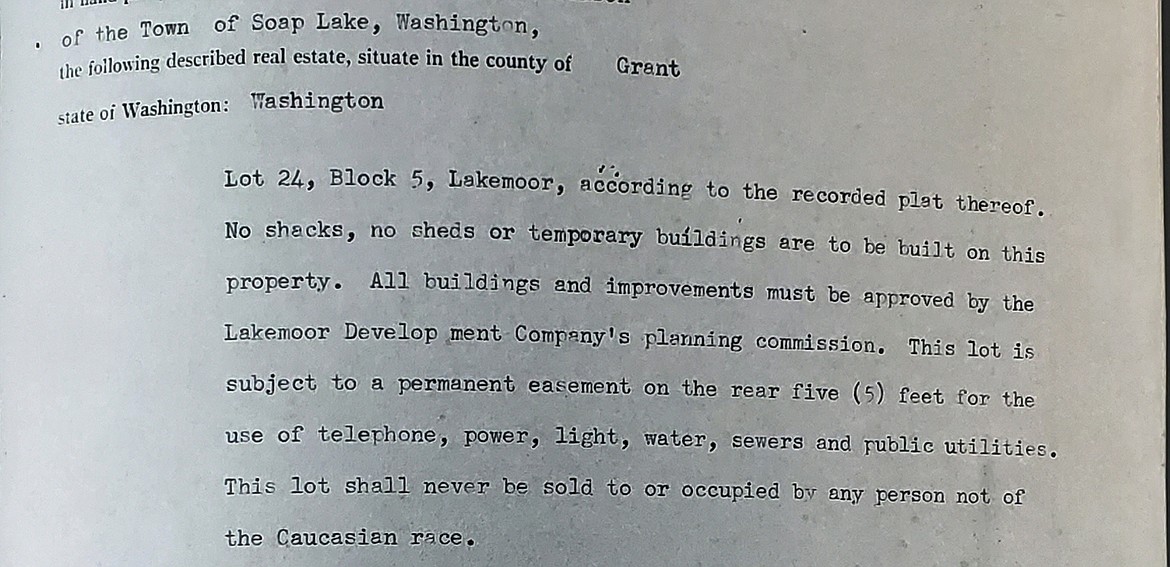

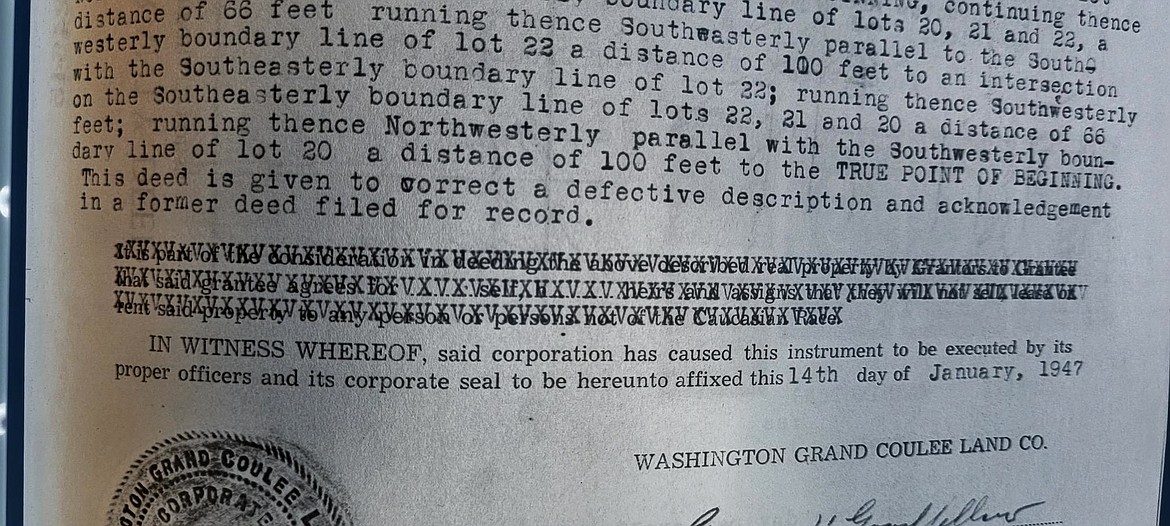

“Starting in the mid-20th century in eastern Washington, and earlier in some other places, developers began adding racial restrictions,” said Dr. Larry Cebula, a professor of history at EWU and managing director of the project. “These typically read ‘only members of the white or Caucasian race will live here.’ There’s usually a kind of codicil saying ‘excepting servants thereof.’ So if you had a servant who was a person of color, they could live there. Most of the racial covenants we find in eastern Washington reads like that. Sometimes there’s a list of who can’t live there: ‘No Negros may live here,’ ‘no members of the Asiatic race,’ – something like that. The language varies, but it’s usually only whites.”

That’s part of what the Racial Covenants Project at Eastern Washington University is discovering about many properties in the region, including in Grant and Adams counties. As the population grew, many land developers wrote issued race-based covenants for neighborhoods they were developing. They no longer carry any legal weight, but they’re still there, in courthouses across the region and the country.

A law passed last year by the Washington State Legislature directed that these covenants be sought out. The Racial Covenants Project at EWU has been steadily researching the 20 counties of Eastern Washington, while a parallel group at the University of Washington does the same for the West Side. So far, the teams have found racial restrictions on more than 50,000 properties statewide. Given the population balance of the state, the majority of these are in the Puget Sound area. Research in Grant County is still a work in progress, but as of Thursday 80 documents had been found to carry some kind of racially restrictive covenant, in Moses Lake, Soap Lake, Ephrata and Electric City. A complete survey of Adams County properties found only one restricted neighborhood: the area around the Ritzville Municipal Golf Course.

Unofficial practices

The question of who can live where in the United States has a long history. More than half a century after the Civil War, the 1917 U.S. Supreme Court decision “Buchanan v. Warley” established that government entities like municipal or county governments couldn’t dictate which neighborhoods minorities could or could not live in. This prompted private developers to include covenants – contracts between private individuals – when selling residential property to prevent minorities from owning or renting a home in a given neighborhood.

These covenants were usually attached to the property by the developer, mandating that any future purchaser had to be white. The wording varied as occasionally did the minorities being discriminated against. Sometimes Asians were specifically named, sometimes it was only Blacks, and occasionally Jews or Catholics might be prohibited.

If a homeowner sold to a member of one of those groups, his neighbors were entitled to take legal action to prevent the sale. These racial covenants became legally unenforceable in 1948 with the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in “Shelley v. Kraemer,” but discriminatory practices remained, even if only tacitly executed.

Practices like redlining, where banks refused to extend mortgages in certain neighborhoods, and “gentlemen’s agreements,” unofficial verbal commitments among neighbors, continued to keep neighborhoods segregated. It wasn’t until the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was enacted that racial discrimination in housing was explicitly prohibited.

“It’s important to emphasize that these legal restrictions are not the only way that segregated housing was established and maintained in the United States,” Cebula said. “There’d be much less formal things like a bank won’t give an African American a mortgage in a certain neighborhood. Or real estate agents won’t show a Hispanic family a house in a certain neighborhood. Neighbors might make a person of color feel uncomfortable through various levels of harassment. There’s a lot of ways this stuff happened.”

Not so common

In Moses Lake, residential neighborhoods where racially restrictive covenants have been found include the Capistrano Park development near Peninsula Elementary School, as well as the Lakeview Terrace, Knolls Vista, Crestview and Guffin-Eccles neighborhoods.

Ephrata Heights in the eastern part of Ephrata and Grandview Heights, located between Statter and Patrick roads in the western part, also carried racial covenants. Some of these were platted with racial restrictions even after the Shelley decision, the provisions unenforceable but enshrined in writing anyway.

“They’re signed off on by the county commissioners and people like that,” Cebula said. “And if you run these people through a newspaper search or something like that, you often find that they are quite prominent. At the same time, and I can’t make this point strongly enough, not everyone was doing this back then.”

He explained that researchers spent hours going through what may be an 800-page book from the era such restrictions were more common and only one or two such covenants would be found. Some later deeds have the restrictive covenant crossed out, and others have clauses inserted explicitly removing any racial restriction.

“This was not standard practice. This was something some people went out of their way to do,” he said.

Searching files

Finding the documents has been a herculean task, according to Dr. Tara Kelly of EWU, a sociocultural anthropologist and the project director who is heading the team of students and volunteers digging through the archives.

“We’re looking at digital and in-person physical deeds and plat maps,” Kelly said. “Our first phase of research was to look at the digital plat maps; they’re held on the DNR website.”

The process is complicated and painstaking, involving pulling township and range numbers as well as plat maps and other documents, then poring over those looking for racial restrictions, she said. It also involves a bit of travel, going to various auditors’ offices across the state.

“They open up their archives to us, and we look between 1920 and 1960 at their many, many volumes, about 600- to 800-page volumes, of which we’re looking at anywhere from 10 to 130 different volumes. We page through those and we look for different deed records,” Kelly said.

Sometimes the restrictive covenants are blatant with numerical listings that include the racial covenant. In other cases, the language of the race restriction is buried in documentation and takes time to identify, she said.

“So that’s our in-person, very time-consuming research of the physical records,” Kelly said.

The process is much faster for counties with digital records thanks to an optical character recognition program specially created for the project by a developer in Seattle.

“Instead of looking at each and every document with our eyes, we’re able to have this software go through it and pop up what may or may not be an actual racial covenant,” Kelly said.

Even those results need a manual review though.

“Sometimes there’s false positives like ‘white heifer’ or ‘Mr. Black’ or ‘the red train car.’ So we have our team go through after the OCR and manually, (with) human eyes. Check each and every one of those. We’ve been very busy.”

Clearing the air

So how can homeowners get rid of these Jim Crow holdovers attached to their property? The bottom line is, they can’t. Once a document is attached to a piece of property, it’s there permanently.

“A few years ago, a homeowner… sued my office and me in my official capacity and wanted the original document removed and destroyed,” said Spokane County Auditor Vicky Dalton, who’s been working closely with the Racial Covenants Project. “And the (Spokane County) Superior Court said, ‘No, the auditor doesn't have the authority to remove a document and definitely doesn't have the authority to destroy a document.’ Then it went to the court of appeals, and then it went to the state Supreme Court, and the original opinion was upheld each time.”

How to manage such records and remove the covenants fully is a question still unanswered.

“The legislature is working with the auditors and with the Department (of Natural Resources) who does all the mappings. Everybody's working to identify these and find the proper way to redact them,” said Adams County Auditor Heidi Hunt. “But as an individual, I do not believe that you can go back and make a change to any deeds that were recorded before your deed.”

The matter is complicated because a property owner’s documentation isn’t tied solely to his or her own lot. The chain of title that establishes ownership has to remain consistent and unbroken, or there’s a danger of the owner’s title losing its validity. When a development is platted, any legal documentation that is attached to the plat as a whole will carry over to the individual lots once they’ve been sold. If an individual owner changes a document that refers to the development as a whole, as with a protective covenant, it creates an inconsistency in the other owners’ chain of title.

“We're still trying to figure out some of the processes we have to do because we've never removed documents before,” said Dalton. “It's not something you do in recording because when you put something on the shelf, man, it stays there. It's there forever. Our timeline is not 60 years’ retention, or 30 years’ retention; our timeline literally is forever, until our civilization collapses. So we see things a little differently as far as preservation.”

There are two ways a homeowner can deal with a racially restrictive covenant, Dalton said. One merely involves adding a document to the property’s chain of title declaring officially that any racial covenants aren’t binding.

“When this came up, it was directed to me,” she said. “And so we worked with the advocates and the legislators to create a process to allow a homeowner to file what's called a modification. That modification document is pre-prescribed, it's got a basic format, and they just need to fill in the blanks and sign it and it's recorded for free . . .And it just basically says, ‘Somewhere in my chain of title is an invalid racially restrictive covenant, and it is invalid.’ That's all it says. It doesn't take it out, doesn't change any records, it just calls it out to say it’s somewhere in the chain of title.”

The other method is a little more involved and requires going to court, Dalton said. A homeowner can submit a form that creates a new version of the existing document, with the restrictive covenant redacted and use it to replace the original document in the auditor’s file with a notation that the document has been changed. The original document will then be archived in Olympia.

That process allows homeowners to take court action and update to a title that has the racial restrictions redacted – as though the document is a brand new filing for the property, Dalton said. The original is stored as a historical document, but the official, active document is maintained locally and legally.

So far nobody has actually gone through that process, Dalton added. Unlike the modification, replacing a document with a redacted one costs money and hiring a lawyer is recommended.

Similar projects to identify racially restrictive covenants have been started in California, Missouri and Minnesota, Cebula said, but Washington is the first state to take legislative action to address the matter.

Past meets present

Racially restrictive covenants may be an anachronism, but their presence serves as a reminder that the racist past isn’t as far in the past as many would like to believe.

“I was shocked that we had one (restrictive covenant),” Hunt said of Adams County. “But I guess maybe I wasn't shocked, because I've lived in Ritzville my whole life and you know, those were different times back then.”

Dalton expressed similar sentiments.

“When you talk to people who own a home, and they look through their chain of title, and they see a restrictive covenant that would have prevented them from owning the home just 40, 50 years, 60 years ago, it's powerful,” Dalton said.

She added that she’s met with those that have looked back at their property documentation and changed their attitude about the idea because it then becomes more of a reality and less of a theoretical situation because they wouldn’t have been able to own their homes in the past.

“Some people say, ‘Oh, you're erasing history if you go back and remove these documents,’” Cebula said. “I say no, we're not erasing history. We're making history.”

Joel Martin can be reached via email at [email protected].