Water and power

GRAND COULEE — The editors of Life magazine could not hide their suspicion that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had decided a trip to check on a project was an excellent excuse to get out of town.

There was a capital-S Scandal in Washington D.C. the early days of October 1937, but Roosevelt wasn’t around to answer questions about it. He was somewhere in the remote wilds of Eastern Washington, examining the progress of a massive undertaking designed to revolutionize the economy of Washington state. The structure rising across the Grand Coulee was going to dam the Columbia River, provide electricity for tens of thousands of homes and water to irrigate millions of acres of farmland.

Ambitious. Life’s editors voiced the possibility it might be too ambitious.

“Audacious high dam proposal”

Looking back at the past it’s frequently assumed there was only one way for events to turn out. Grand Coulee Dam was built, and it does provide electricity and irrigation water. But Life’s editors didn’t know how the story would end when they sent a team to document the construction site. The Grant County Commissioners who heard a slightly whacky proposal in the fall of 1917 didn’t even have the benefit of a construction site.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s history of the Columbia Basin project, the local effort began in the office of Ephrata attorney William “Billy” Clapp in the summer of 1917. Clapp and his friends were talking about the need for more food, and of course, a roomful of Ephrata guys believed Grant County had the potential to be a productive farm country. It just lacked reliable water.

One of the group observed the Columbia River was right there, and there was that big wide canyon upriver, the Grand Coulee. Put a dam across that, and — hey, that desert would bloom.

It was an idea they returned to over the summer, and eventually approached the commissioners. According to the Bureau of Reclamation, the commissioners thought it was kind of nuts. They agreed to let the county’s deputy engineer go up the Coulee and take a look. Only keep it quiet, the commissioners said.

The engineer, Norval Enger, reported back that it was possible, and might even be a good idea. It would be expensive, though, way more than Grant County could afford. Maybe more than anybody could afford.

Clapp and his friends were talking to other people around Ephrata, one of whom mentioned it to Rufus Woods.

It became a North Central Washington legend, that day in July 1918 when Woods rolled into town. Woods was the owner-publisher of the Wenatchee World, looking for a story. As Woods told it, he talked with another Ephrata business owner, who casually suggested he drop by Clapp’s office. Woods did, listened, then published a story about Clapp’s idea, which he called an “audacious high dam proposal” July 18, 1918.

“Latest and newest and most ambitious idea,” Woods wrote, according to the Bureau of Reclamation.

It was so audacious it took a long time for anybody to think it could be possible. The Pacific Northwest didn’t have that many people - who would use all the electricity? Who would operate all those farms?

A dam across the river would end all the upstream salmon runs, too. That would have a big impact on the Native Americans that lived around the Coulee. But salmon and salmon runs were low on the priority list.

Woods, Clapp and James O’Sullivan, an attorney in Moses Lake, kept pushing, promoting and talking to government officials. There were other proposals, such as irrigating the Basin with water from Lake Pend Oreille. That one too had passionate advocates.

Then there was the sheer size of the thing. Had the guys promoting it — they were known as the “dam college” — even looked at that canyon? It looked like it was a mile wide. (Actually, the finished dam is 5,223 feet long, or almost a mile wide.)

The dam college guys kept insisting it would work and would be beneficial to the region and the country. With claims and counterclaims and dueling projects, the feds did what governments do and commissioned a study.

The work fell to John S. Butler, an Army major in the engineering corps who surveyed the whole river, starting in 1928. (In a notable example of economy, Butler and his team spent a little more than half the money allocated.)

He submitted what was called a 308 Report in 1931. Butler concluded a dam across the Grand Coulee could work, both in terms of electrical generation and irrigation. In 1931 nobody was listening.

The Great Depression was hitting hard. Jobs were scarce, money was scarce, even government money. Then-President Herbert Hoover wrote in a February 1932 message to Congress that the last thing the country needed was more farmland, according to the Bureau of Reclamation.

“Roosevelt the Builder”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt saw things differently.

Life’s editors summed it up by saying Roosevelt envisioned a future where electricity was cheap and people could use it to build better lives. The Washington Legislature started the ball rolling by allocating $377,000 to do preliminary work at the site. The federal government followed with a contract for a dam about 350 feet high. That wasn’t quite what the dam college guys had advocated — it would provide water for electricity, but none for irrigation.

The contract for a 350-foot dam was awarded in 1934. The contractors were a consortium of four companies — the project was so big one company couldn’t do it alone.

Roosevelt changed his mind, however. In 1935 he asked Congress for, and received, money to build a much bigger dam, 550 feet high. That would provide water for irrigating the Columbia Basin from Wenatchee all the way to Tri-Cities.

Men came from all over the country to build it. Washington state spent more than $600,000 to build roads and bridges to the site. A purpose-built railroad was constructed.

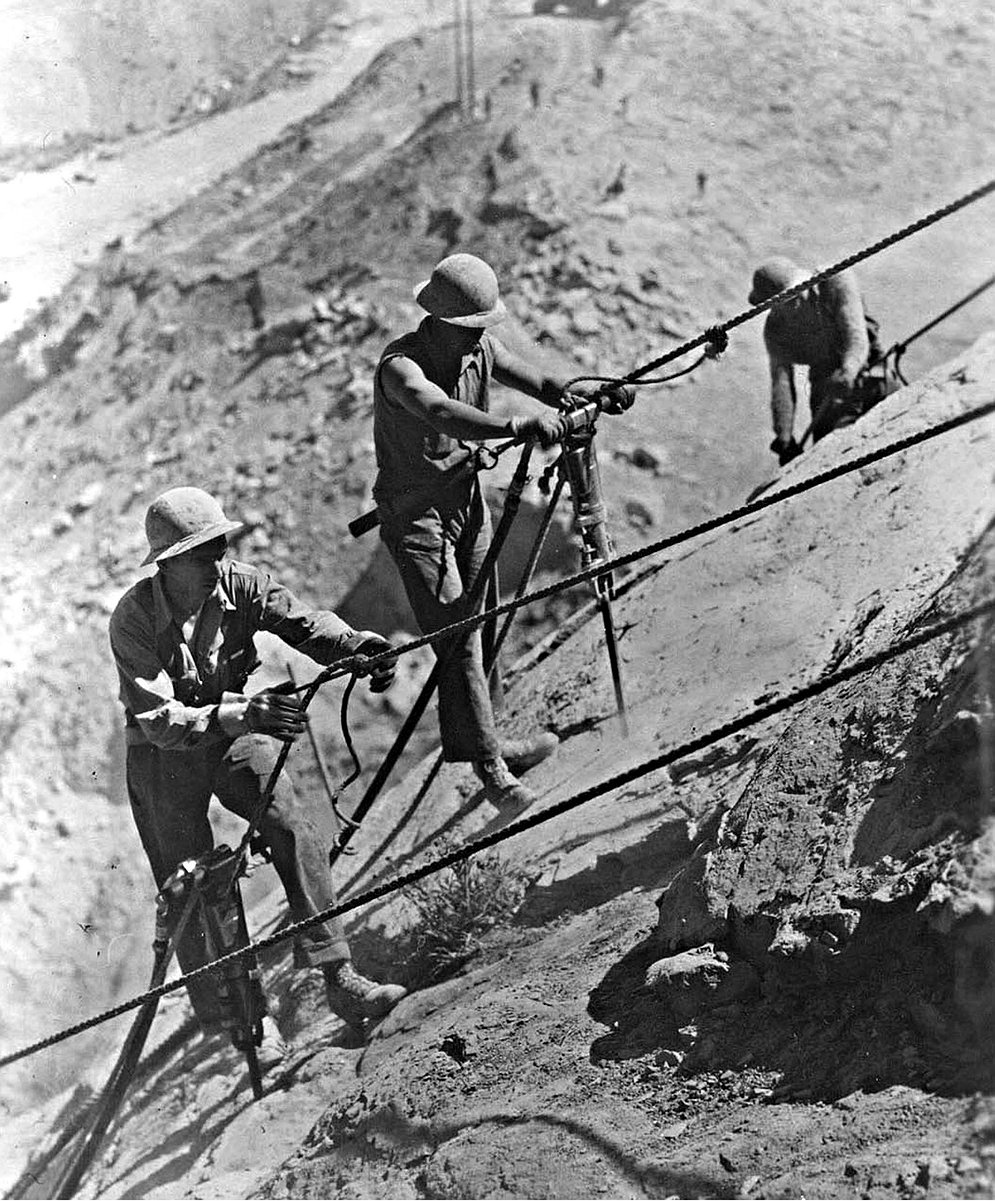

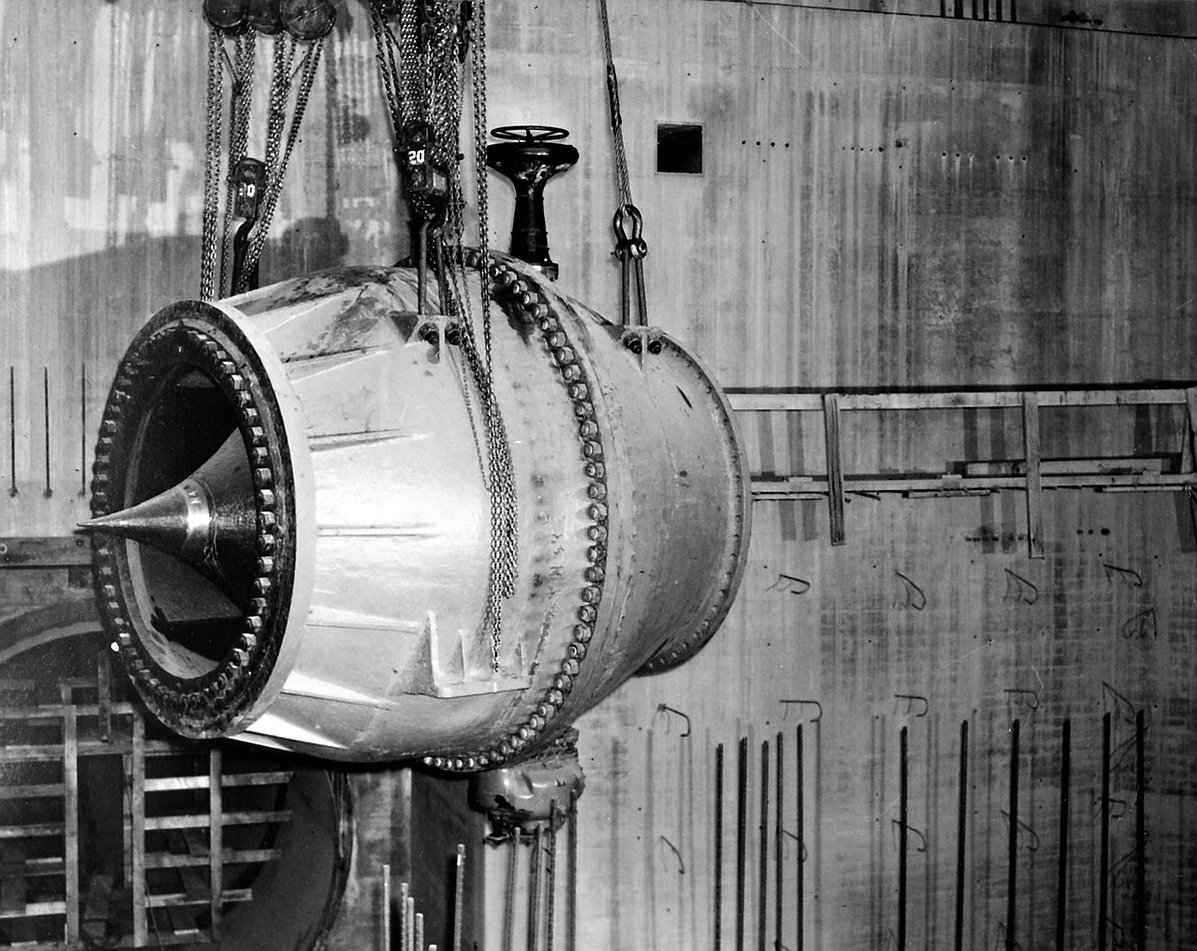

The workers built temporary structures to control the flow of the river while they excavated down to the bedrock. (One reason the site was so good was that the bedrock is very sturdy, according to the Bureau of Reclamation website.) They excavated the hillsides to get down to solid rock. That required freezing part of the hillside to keep it stable during excavation.

Then they started pouring concrete, block by block. Governor Clarence Martin showed up to pour the first load of concrete in December 1935. The crews moved the excavated sand and dirt out, and building materials in, by means of conveyor belts. Setting the concrete required running cold water through pipes embedded in each block to control the temperature as it cured. Life’s editors said the engineering challenges were a known quantity and had been solved long before. But whether or not Roosevelt was right, whether Grand Coulee Dam would deliver what he wanted, was still unknown, they said.

Construction was estimated to cost about $200 million when — or if, the editors added — it was finished. It actually ended up costing about $300 million in 1940s money.

The Bureau of Reclamation estimates that would be about $5.5 billion today.

The project was dependent on the goodwill of Congress, which could’ve killed it at any time. Life’s editors estimated it would take about half a century, until 1990 or so, before it was paid off. By that time, they observed, people would know whether Roosevelt had been right or whether it was all as wasteful as the pyramids of Cheops.

Was Roosevelt right?

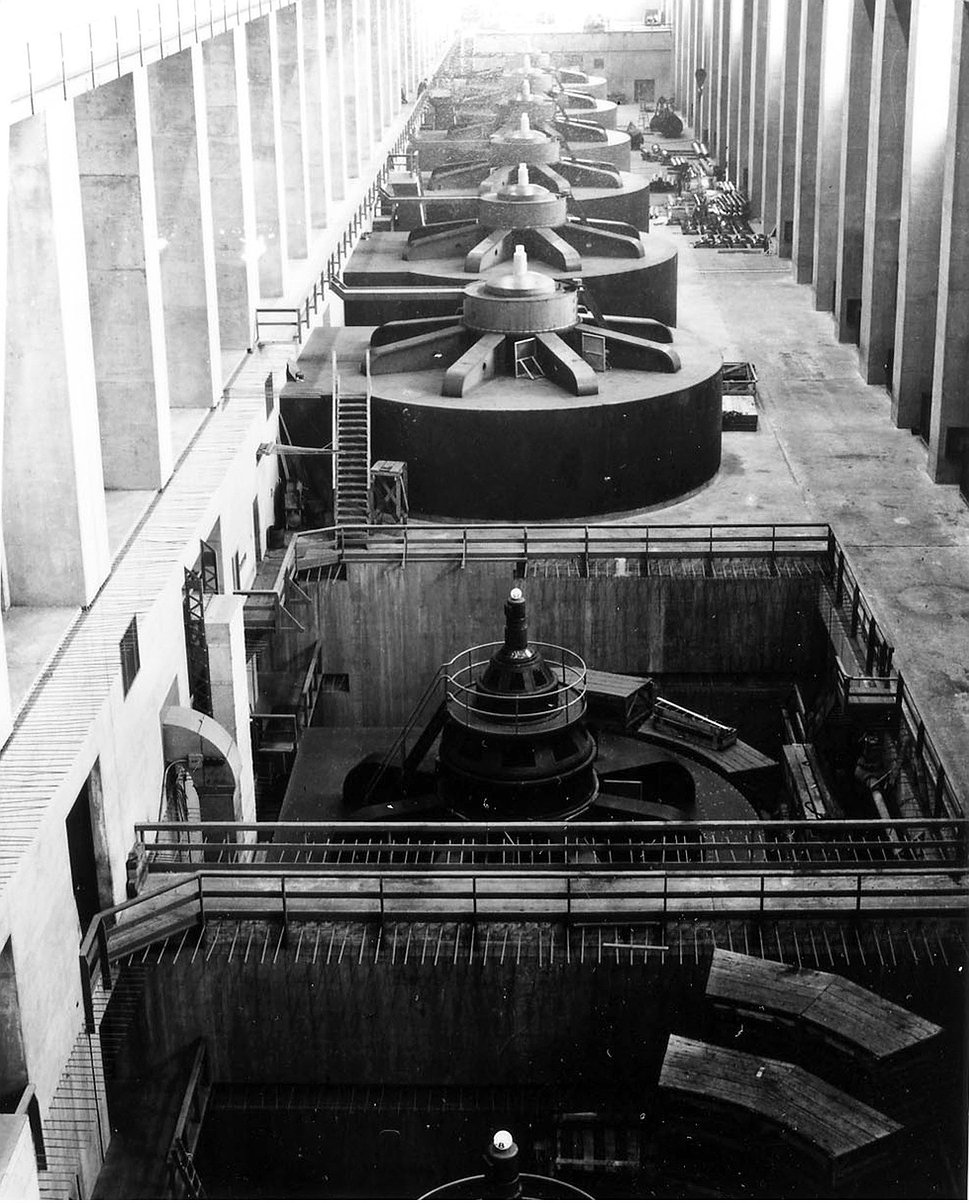

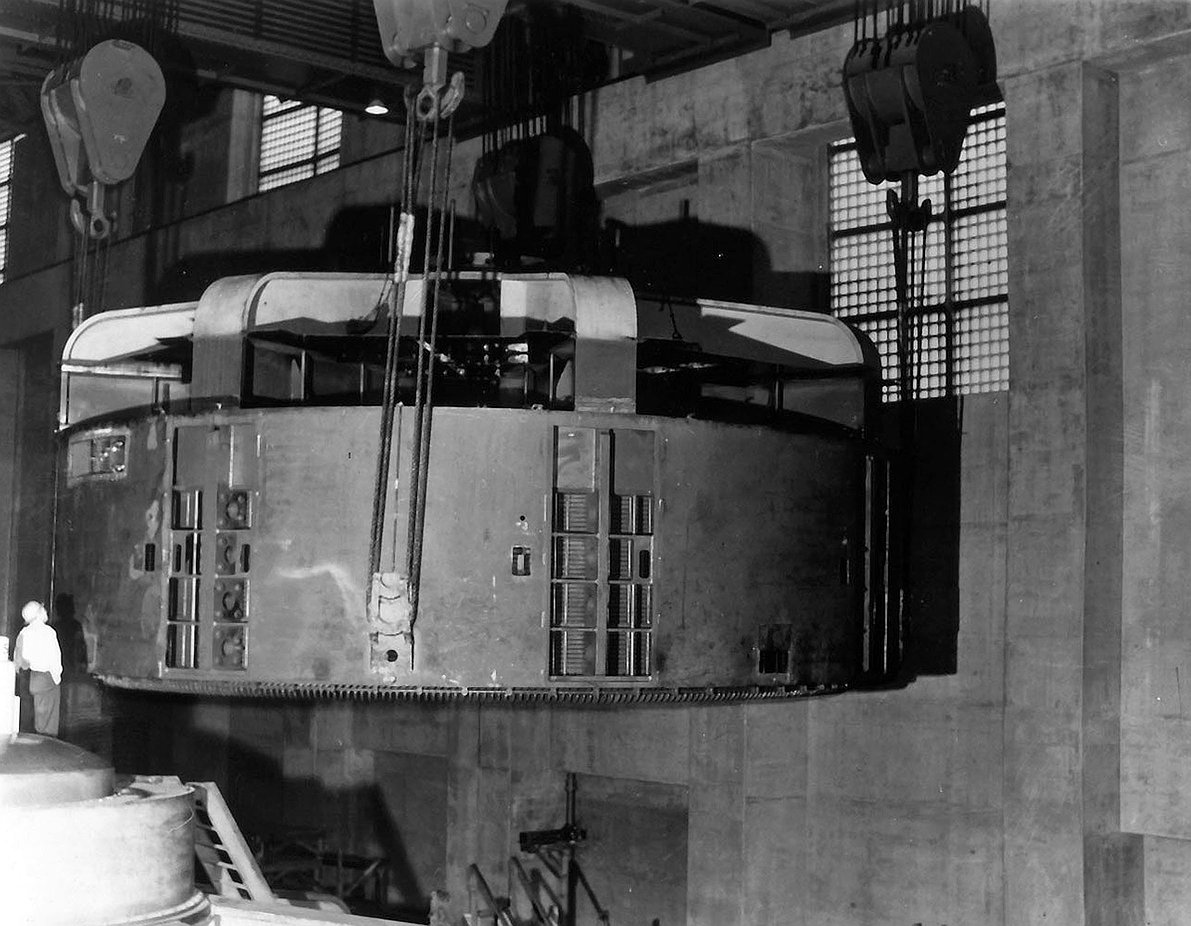

The people who worried that there wouldn’t be any use for all that electrical generation were wrong - World War II saw to that. The need for power was so great that the irrigation phase was delayed until after the war. Electrical demand was such that a third powerhouse was added in the late 1970s.

When the irrigation water came it did attract farmers; currently, there are about 670,000 acres in cultivation throughout the Basin. That’s about half the original estimate since the project isn’t complete.

Parts of the structure are paid off, but continuing construction has added to the bill, and there’s continuing maintenance as well, according to the Bureau of Reclamation. Each irrigation unit also is part of the project, and those costs are added to the overall total. Reclamation estimates that the last irrigation unit of the current phase will be paid off in 2044.

The salmon runs are no more, and the way of life of the Native Americans upstream that depended on them was changed forever. Hatcheries were built below the dam to help offset the loss, with a portion of the fish allocated for the tribes affected. A portion of the proceeds of power sales are allocated to compensate the members of the Colville Confederated Tribes and Spokane tribes.