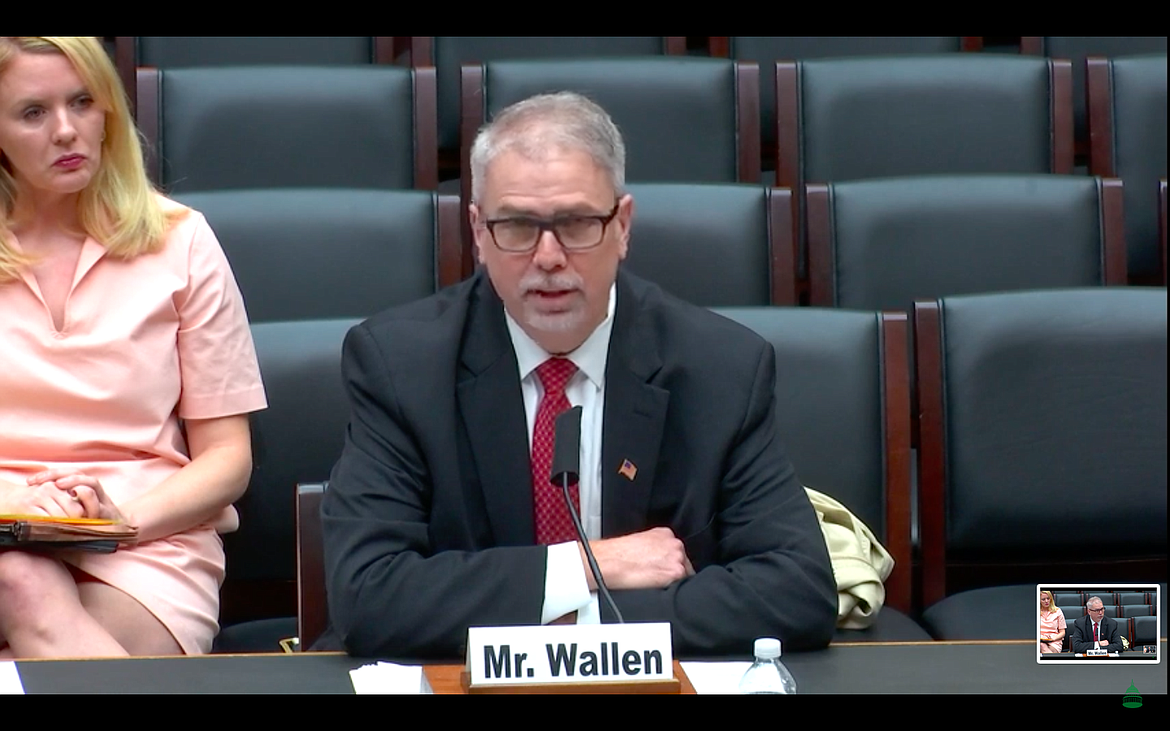

Grant PUD chief testifies before House

WASHINGTON, D.C. — With demand for electricity in Grant County growing, federal energy regulators need to make it easier for hydroelectric generators like the Grant County Public Utility District to relicense dams and improve power production, PUD General Manager Richard Wallen told members of the House of Representatives on Thursday.

Become a Subscriber!

You have read all of your free articles this month. Select a plan below to start your subscription today.

Already a subscriber? Login