Mistaken identity: Know what you’re seeing when hiking the Basin

A number of Washington species make the news frequently. Hot button animals in the area lately come in the form of the Columbia Basin pygmy rabbit, the northern leopard frog and the gray wolf.

Each time a story runs on one of these animals, the Department of Fish & Wildlife gets calls from people claiming they’ve seen them on hikes or even their backyard, said WDFW pygmy rabbit biologist Jon Gallie. Upon investigation, though, it’s almost always a bust.

The pygmy rabbit is the smallest rabbit species in North America, emergency-listed as endangered in Washington in 2001. The 2021 WDFW winter survey indicated around 40 active burrows in the Beezley Hill Nature Preserve area, with total population numbers less than 100.

A lot of people think they have pygmy rabbits in their backyards, Gallie said, when it’s likely a Nuttall’s cottontail.

Pygmy rabbits are smaller, the largest being around 11 inches, but this can be tricky to differentiate between a young cottontail. Both rabbits range from gray to gray-brown.

One of the easiest ways to tell them apart is in the name -- while both have small, inconspicuous tails, the Nuttall’s cottontail is white and larger than the pygmy rabbit’s, and the pygmy rabbit’s tail is the same color as its fur and nearly invisible.

Another indicator is location. The cottontail isn’t endangered, so if the rabbit is spotted in a yard, orchard or anywhere far from the Basin’s dense sagebrush, odds are it’s not a pygmy.

Northern leopard frogs, which used to be abundant across the state, landed themselves on the endangered list in 1999. A recent survey found 200 breeding females, determined through genetic assessment, in the only population remaining: south of the Potholes Reservoir, said WDFW northern leopard frog biologist Emily Grabowsky.

Northern leopard frogs have slender bodies, thin waists, long legs and smooth skin. Their bellies are cream-colored and their backs are brown or green, with distinct round spots in two or three irregular rows, each with a light border.

Leopard frogs are easy to confuse with bullfrogs and Columbia spotted frogs, especially as tadpoles, as they occupy the same range. According to the WDFW, leopard frogs lack the dark smears on their tail fin that bullfrogs have, and also have abdominal muscles that are nearly transparent.

Another way to tell is the eggs. Unlike Columbia spotted frogs, leopard frogs do not lay eggs in multiple clusters, but rather in a single pile attached to underwater vegetation.

The gray wolf, a native Washington species, was nearly eradicated from the state in the early 20th century, according to the WDFW. Since, they’ve been returning on their own from nearby states and provinces.

Since 1980, gray wolves have been listed as endangered in the state. However, the population has been growing for 12 years straight, and current wolf numbers in Washington are higher than they’ve been since the most recent recovery plan was adopted in 2011.

At the end of last year, WDFW counted 132 wolves in 24 packs and the Colville Reservation reported 46 wolves in five packs.

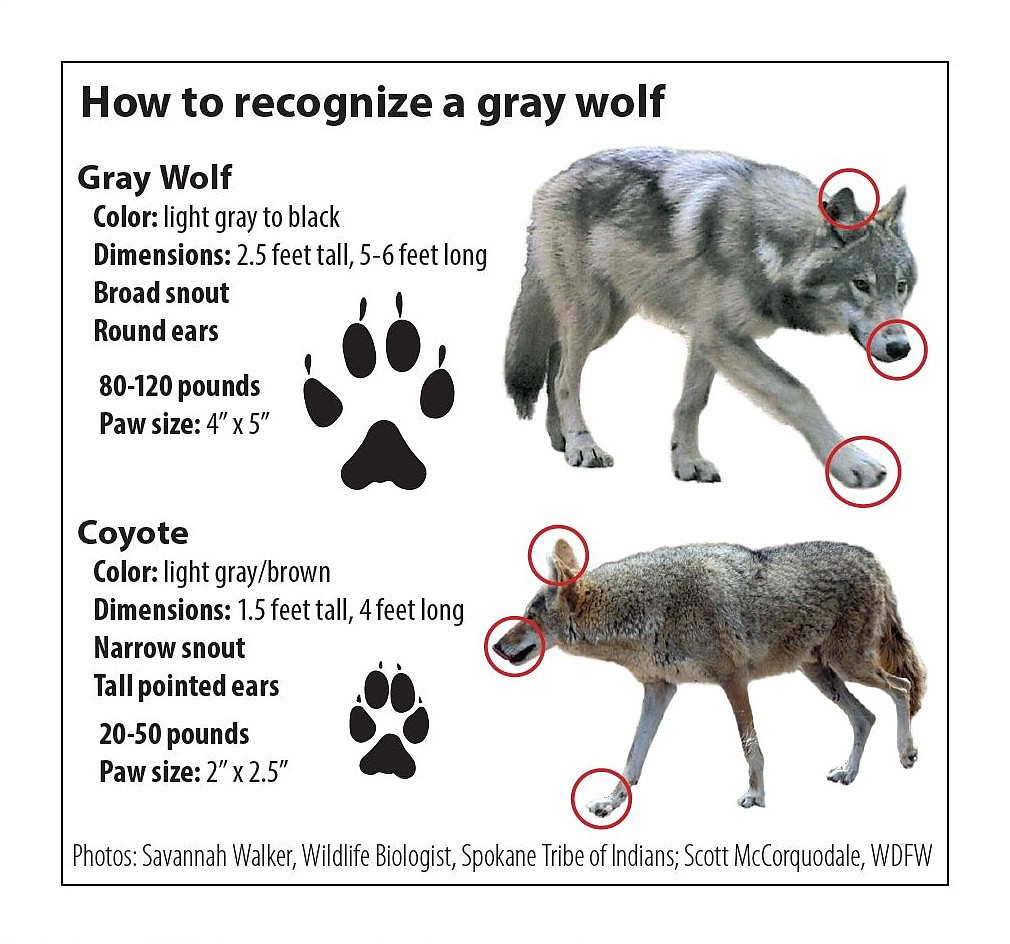

At first, the difference between gray wolves and the coyotes abundant in Washington may seem obvious: wolves are typically about twice the size. However, the size variety between males and females and young and old wolves has large overlaps with coyote sizes.

While gray wolves can get very dark in color and coyotes very brown, they also come in varying shades of gray and can appear quite similar.

The best way to tell comes down to the nitty-gritties: wolves have larger and blockier muzzles than coyotes, shorter and rounder ears and shorter and bushier tails.

Paw prints are often quite similar, the only difference being a wolf’s can be much larger. The difference in tracks between a wild dog and a domestic dog is not in shape but in behavior. Wolves often show a direct, energy efficient and purposeful route, whereas domestic dogs often meander about.

To properly identify a sighting, or for more information in general, visit wdfw.wa.gov.

Sam Fletcher can be reached via email at sfletcher@columbiabasinherald.com.