Compassion, empathy and pepper spray: Quincy police officers learn de-escalation techniques

QUINCY — Gary Amaral is anxious.

A late-January graduate of Washington’s Basic Law Enforcement Academy in Burien and a new sworn-in officer with the Quincy Police Department, he’s still going through training.

Last week it was defensive tactics. Today, on a clear and not-so-cold Thursday afternoon, it’s oleoresin capsicum — otherwise known as pepper spray.

Amaral doesn’t just have to learn how to use it. He also has to learn what it’s like to get sprayed. And then do police work against a hostile opponent, fending off an attack and handcuffing someone, for three minutes afterward.

“I’m a little nervous for that,” he said. “I don’t think anyone can actually prepare for that.”

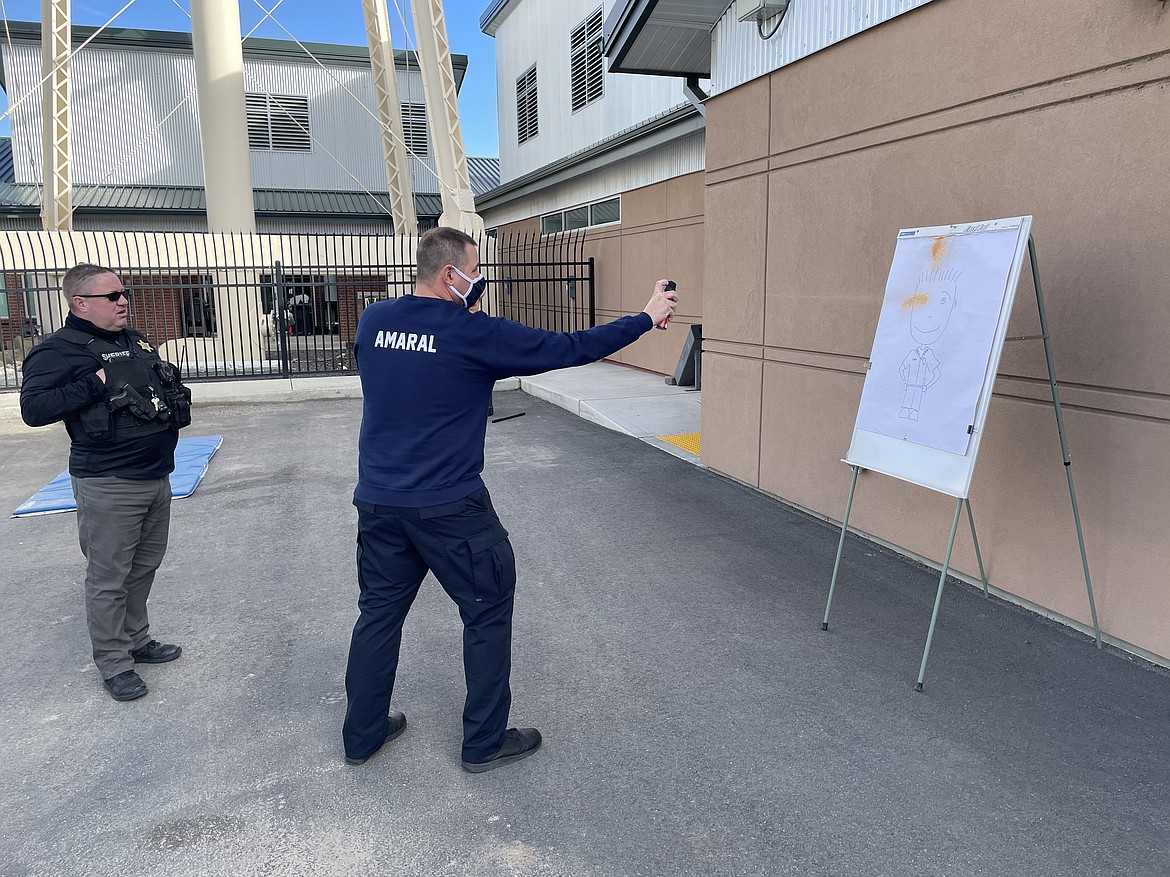

Quincy Police officers gather in a small parking lot behind the department on First Avenue Southwest and underneath one of the city’s giant water towers. Grant County Sheriff’s Office Lt. Dean Hallett, who has trained officers for years on the proper use of pepper spray, shows Amaral how to aim at the eyes of a smiling drawing that bears something of a resemblance to the cartoon character Doug.

Know where the wind is, Hallett reminds Amaral, because the spray can always blow back on you.

It’s part of every law enforcement officer’s training, Hallett said, to get pepper sprayed and tasered, so officers understand how their equipment works and what the people they may have to use these “pain compliance tools” on will feel when they get hit.

“Because I got sprayed, I understand what the other person is going through,” Hallett said. “I can empathize with them, I can understand what they’re feeling and why they’re feeling it, so I can help them.”

It’s survivable, Hallett said, so an officer who has gone through this can tell a suspect they are going to be okay.

“It creates credibility for the agency and the officers,” he said. “It’s so safe we’re willing to do it ourselves.”

“Sometimes, when we spray, we can get exposed, so we do survival tactics. Wiping it off, water and wind,” Hallett told Amaral before the training. “This is to let him learn and understand.”

It’s also a reminder if he’s just pepper sprayed someone, a police officer has a duty to provide care as well, Hallett added.

With the cartoon drawing dripping red pepper spray, Hallett tells Amaral it’s time. Amaral stands and Hallett aims the pepper spray at his face.

“Open and close your eyes,” Hallett said. “I’ll count to five and then spray you.”

He actually sprays Amaral on three.

“I knew he wasn’t going to wait,” said Quincy Police Chief Kieth Siebert.

Amaral doesn’t scream, doesn’t cry out, but just stands there for a moment, clearly in pain, eyes closed tight. He then remembers to wipe the pepper spray from his face with the sleeves of his sweatshirt.

“Good,” Hallett said, leading him to a dummy and handing him a baton. “Now, go subdue the suspect.”

Amaral grabs the baton and begins beating the dummy as Hallett slowly dodges and parries with it, constantly telling Amaral to open his eyes and pay attention to what he is doing even with all the pepper spray in his face. After two minutes, Amaral moves to handcuff Quincy Police Detective Stephen Harder, who is already prone on a mat. Amaral squints, fumbles a bit, tries not to do too much with his eyes open.

And then … a hose of cold water on his eyes and face as Hallett gently helps him clean up.

“It’s hard to breathe,” Amaral said a couple of minutes later, as he sits in front of a big box fan.

It was all he was up to saying. It would be about 15 minutes or so before he would fully recover.

“This is a rite of passage,” Siebert said. “We’ve all done this.”

Siebert described Amaral, 31 and the married father of two, as a very “cerebral” police officer who has a good heart and understands the “why” of police work.

“That allows them to think on their own and shows they can work through a problem, especially nowadays when you talk about duty to intervene and de-escalation. You can’t always just do things by the textbook,” Siebert said. “Sometimes you gotta step outside (the situation) and do what is going to work.”

For Siebert, it’s all about having officers with emotional intelligence who understand that not everyone needs to go to jail.

“In fact, most of the time, our job is more of a counselor role than anything else,” Siebert said. “To steer people in the direction they need to go in order to get help.”

Amaral uses that word de-escalation a lot, and for him, it means being able to mentally distance himself and not react emotionally when someone is very emotional — and violent — toward him. As a Chelan County corrections officer for three years, he had ample opportunities to learn that skill.

“In corrections, it’s all about de-escalation, it’s all about not having that ego, not having that that pride,” he said. “It’s all about taking somebody on their worst day and helping them through it if you can, or getting them to a place where they’re safe and everybody else is safe.”

It was the gifts he has honed for years, first as the service manager of a Honda dealership, and then as a corrections officer, that got Amaral’s academy classmates to give him the Patrol Partner Award as the graduate they’d most want to “have by your side,” he said.

“I was very shocked and very honored,” he said. “Of all the awards at the academy that I could, I truly feel honored for winning this.”

Siebert said Amaral is one of several “good officers” the Quincy Police have hired from the Chelan County Jail.

“He’s very thoughtful in his words, very much community-oriented, and he can’t wait to get out here and partake in some of the events we do,” Siebert said. “Whenever we get to do them again."

Charles H. Featherstone can be reached at cfeatherstone@columbiabasinherald.com.